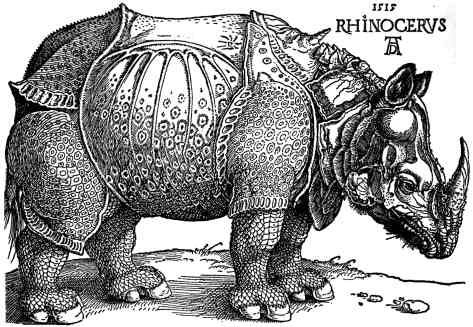

There is a statue of a rhinoceros outside of the School of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, where (incidentally) I do not have a job. It looks like a rhinoceros—you immediately register it as such, not as a whacked-out version of something that started in some artist’s mind as a meditation on rhinocerosity. But if you look more closely, there are some telltale scrolls on its body armor, almost like calligraphy or runes. Interviewing for a job a few months ago at the SMFA, I recognized the design immediately: the sculpture was the three dimensional manifestation of a woodblock print that Albrecht Dürer, the rock star of the Northern Renaissance, had done early in the sixteenth century. And the rhinoceros that he had done was based on descriptions and possibly another sketch; Dürer never saw a live one himself, so he essentially made a hearsay version.

As I stood there in a suit skirt,

about to go in for a second-round interview, I thought about exactly how many

layers of abstraction and artistic license stood between the sculpture in front

of me and an actual, living rhinoceros.

It seemed to me that the actual rhino, the living version that started

this whole chain, in the end didn’t matter as much as the exchange and

renegotiations of ideas that went into its representation.

These are the things you tend to

think about, on the tail end of your art history MA, about to go in for an

interview. Otherwise, you have to think

about the extremely daunting task of getting a job in the arts and how the next

indefinite amount of time in your life is going to be extremely stressful.

Well, okay, you think about that too

(in fact, you never really stop

thinking about it), but sometimes it’s nice to squeeze in some ruminations on rhinos.

But of course, it’s never quite as

simple as a rhinoceros, is it?

As a general rule in art, and I suppose

in other, more far-reaching areas, every abstraction removes something a little

further from its reality (if, in fact, there was a reality to begin with). It keeps getting more and more funny-looking

until the original trace of the thing is gone and you’re not sure of what you’re

looking at anymore. What I wondered was this: how far do you have

to abstract something until it stops being the thing that it was?

If asked, I guess I would have always

defined myself as type-A. Good evidence

of this may be found in the fact that I committed myself at the age of seven to

getting good grades so I could get into a particular college. The ambition that sprung from that peculiar

commitment became a significant part of who I believed I was in the years that

followed. In a way, the abstract concept

of ambition came to overshadow and even replace the commitment that had

inspired it, especially after I did get into that college. I was an ambitious person—and it felt

good. It felt like some sort of a

righteous calling that could justify my intrinsic stubbornness.

After college, though, my ambition,

which had shifted from college to career, took some pretty substantial

blows. But I muscled through, because

that’s what I do, it’s what I’ve always done: I worked a crappy job that led to

a not crappy job, which felt like a reward for my sheer doggedness. I went to graduate school and earned the damn

Master’s and came back looking for the job,

only to find that it was not as near a possibility as I had thought.

So there I was—again—prepping myself

for the long, stubborn haul—again—and the only thing I could think was how

tired I was. It took me a while to

articulate it to myself, and I’m still coming to terms with it, but the issue

essentially comes down to this: I do not feel particularly ambitious at the

moment.

I was absolutely repelled by this

realization: I’m ambitious. It’s what I

do. It’s who I am—or was. Who the hell am I now that I’m not ducking my

head and pushing through, always with my eye on the prize? I demanded these things of myself, angry and

shaken.

Surprisingly, there was a dry but compassionate

voice in my head that answered with another question: “What exactly is this

prize?”

I was more or less stunned into

silence by my own internal voice. Who

knew, right?

At first, ambition was the means to

the end reality: it was how I set about getting the thing that I wanted. But eventually, the abstract concept of

ambition solidified into something I saw as a characteristic, a thing I just

did because that’s what I did. Sure,

there were concrete goals along the way, but as I look back, I wonder about the

things I missed in my relentless pursuit.

More importantly looking forward, when does the ambition end? When, where, and what is enough?

The abstraction had become more

important than the original reality, so I started looking for the real-live

specimen, the original rhino: What exactly is the thing that I want?

Fortunately, I’m a bit better equipped

to answer this question as an adult than I was as a precocious seven year

old. Here's what I came up with:

I want to be happy. I want to genuinely like the thing that I do with my days, and I hope what I do will have something to do with the arts. I want to be in a place where the people I love are nearby and ready for adventures, even and especially the ones that happen in a living room. I’d like to be mutually bonkers about someone, and I wouldn’t mind having a bathtub and hardwood floors.

Will all of these things look like what I had imagined for myself in the haze of ambition? No, probably not. But that’s the funny thing: abstractions are never quite as terrifying and marvelous and satisfying as the realities. Just think of the rhino. It’s still difficult for me not to feel like I’m giving up on something; it feels weak to admit that my own blunt force determination can’t eventually batter down certain realities about dream jobs and other fantasies. And hey, maybe in a couple years I’ll feel the same old itch again (and it’s not as though I’m going to miraculously become less stubborn any time soon). What I hope, though, is that I can keep the reality of what I want in mind, and not let it become obscured in habitual abstractions.

Because I’m fairly certain that had he met one, Dürer would have agreed that a hearsay rhino ain’t got nothing on the real thing.