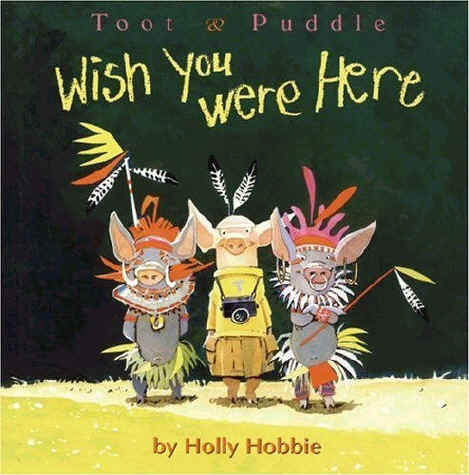

There is a lovely set of children’s books, which I read while babysitting my niece, about two pigs named Toot and Puddle. This charismatic pair of pigs lives in the woods, though one of them enjoys traveling to far off lands. I remember an illustrated scene in which the traveling pig encounters a foreign tribe of boars, which I believe he identifies as the Pig Brothers of Wildest Borneo (or something like that). While the American pig looks on with some trepidation, the Pig Brothers, resplendent with tusks and colored feathers, examine him with expressions of mild amusement and polite interest.

Shortly after I read these books with my niece, I traveled abroad on an art history program and came to understand something very, very important about myself:

I am a Pig Brother of Wildest Borneo.

(No, seriously.)

I came to this epiphany after several weeks of painful observation. I myself traveled as I am comfortable, wearing hiking boots and a Key Biscayne 10K shirt from 1982. By contrast, many people on my trip sprang from that elusive pool of women who seem to have no pores, no bulges, and some sort of direct communion with the Vogue mother ship. It must be stated that some of these women were wonderful human beings, albeit poreless and bulgeless. Nevertheless, in terms of pure aesthetics, in my own mind I suffered greatly by comparison.

That is, until I stopped comparing apples to oranges—or, if you will, pigs to boars.

I do not buy expensive sunglasses, because I sit on them and they break. I do not wear high heels, because I have previously fallen off of low-heeled shit-kicker boots and broken an ankle. I accept that by the time I start to wear a fashion, it has been out of stylish circulation for many months, and I grudgingly acknowledge that while my oily skin does me no favors now, I will probably age well. And yes, I have a regrettable tendency to bulge sometimes.

The good news, though, is that over the last several years, I have begun to worry about these things… well, at least a little bit less than before.

The truth is that I am happiest when I am sitting by a campfire or swimming in a river, soggy undies be damned. My tusks and feathers are Tevas and cargo shorts. Life does not get much better than sitting on a beach with a few beers, my fellow wild Pig Brethren, and a couple of beached kayaks.

I am not pink, I am not polished, and I am more likely to play in the mud than those who are.

Anyway, it takes all kinds.

This is all beatific and self-affirming on the face of it. However, this weekend I walked into a situation in which I was the only one of my kind: pretty, pink, poreless pigs as far as the eye could see. And suddenly I was a little less certain of my tusks and feathers.

I had been hauled into the opening ceremonies of my cousin’s bachelorette party. Citing fiscal constraints (rather than my abject horror), I declined the party bus and table service portions of the evening. I arrived at a screamingly luxurious apartment building, the interior of which looked like a very stylishly appointed mental institution, and entered an apartment in which any woman there could have been the prettiest woman in most rooms.

And there they were, all in one room.

When they started taking off their tops to don the bright pink “party” shirts, I’m fairly certain several boys in the immediate vicinity spontaneously entered puberty. The resident pug was in imminent danger of death by stiletto, and the radiant heat from so much bared, tanned skin made the ambient room temperature soar.

I found myself lurking on the edges of the room, trying to become invisible, though I knew I was painfully obvious in rolled up khakis, flip flops, and a blue-streaked pixie cut. I was that person: poking earnestly at my phone because I had no idea what to say or who to look at, which is not a problem I often have. A few of the women were friendly, but this was clearly a tribal activity, and I was just a random cousin, far out of my own frame of reference. I may as well have been wearing a sealskin parka on Fiji. I felt actively bad about myself and entirely furious with myself for feeling that way.

I think the question comes down to this:

What is it about being surrounded by things that you aren’t that makes you feel bad about the things that you are?

To add insult to injury, my biggest frustration was the knowledge that I didn’t even want these things. The life I lead and the way I look are in line with the things I value. I generally like who I am—I am a Pig Brother! I am happy to be a Pig Brother!

At one point, I fled to the bathroom and examined myself in the mirror. Except for the addition of a bright pink bachelorette shirt, I was exactly the same person who had walked out of my apartment earlier that night. As I looked at myself, it was almost like my vision briefly returned to normal: there I was, looking the way I do—on purpose—and that was just fine. I knew that this return to sanity was fleeting, because I would eventually have to leave the bathroom and go back into the smooth-legged, short-skirted fray.

Thankfully, as the party bus departure neared, I was able to excuse myself and make a run for my Subaru. Before I left, my lovely bridal cousin, who has no pores, no bulges, and a good heart, told me it had meant the world to her that I came. I told her I had been glad to and silently reflected on the things we do and the lies we tell to the people we love.

Back in my own territory, I walked to my apartment in the pouring rain. I had figured by that point that I needed to stop judging myself and just lick my wounds for the night, which one can do to fuller effect when one looks like a drowned rat. I came in thoroughly soaked and very thankful to be back in my own country, the small island refuge of one rather shaken Pig Brother.

What bothered me most about that night was not that I felt out of place—after all, I was out of place—but how small I felt, how inferior. What the hell was going on here? When I had made all of this progress towards figuring out who I am, had I missed some small corner of my personality? In an amongst all the things I believe, was there some traitorous little value that had hidden in plain sight, secretly longing to be someone I very clearly am not?

These are more or less rhetorical questions that indicate how rattled I was. I bank on knowing who I am, on believing that this person I turned into is the most genuine version of myself. I think the thing that frightened me most is that the nasty, niggling insecurities I experienced at the party brought to light the fact that my idea of self may not be quite as whole as I thought. There are fault lines along old injuries from the time before I embraced the inner tusks and feathers, when I still wanted to be blonde and devastatingly pretty and before I realized my own beauty takes a different tack and always will.

Maybe it’s naïve to think I would ever completely shed those old desires, even if I’ve come to value and want something very different for myself. After all, I came to be who I am now in part because I eventually did something constructive with those insecurities, hauling them out into the sun and realizing with some surprise that the things that I thought were so embarrassing were actually just the things that made me interesting.

And so a Pig Brother was born.

I hate the idea that I would only be comfortable around people who are just like me—how boring is that? In the end, though, I know that all of this is just some learning curve or another, so perhaps in case I’m feeling a bit less than enlightened in certain pretty, pink situations, I should have an escape route on hand. In the case of my lovely cousin’s wedding, I was pleased to discover that there is a swimming hole in the woods within walking distance of the reception.

So if I really need to, I can return however briefly to my own element, kicking off my heels and playing happily in the mud.